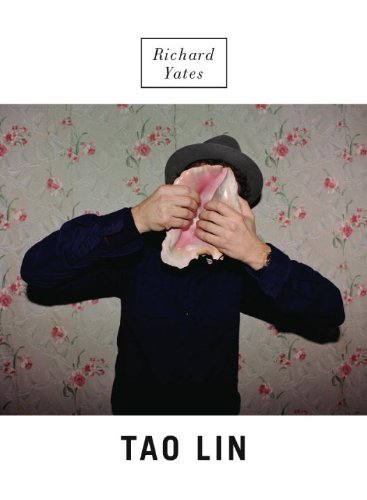

Kittysneezes and A Gathering of the Tribes

Since I have like three venues to publish it in, and I told Tao I needed a galley, I feel obliged to write a review of Tao Lin’s novel, Richard Yates. I don’t think I will ever read anything by Richard Yates. Reading Tao Lin has a way of erasing any literary knowledge one had. I eagerly anticipated this release after reading Eeeee Eee Eeee and Shoplifting from American Apparel. He sold shares in this novel to publish it and not have to work at a vegan restaurant while he was writing it.

I feel not conscious enough of how I’m mimicking Tao Lin’s Style. Tao Lin’s Style is infectious and hypnotic. Writing about Tao Lin in Tao Lin’s style, as The Observer, or rather Christian Lorentzen, did, is hard to resist. I think the Observer was lazy. I approve of that laziness. Of course, as with Hemingway, another “bad” writer whose parody comes easy, and whom Tao Lin namechecks as much as Yates, and includes in the index, the style slips in anyway. While reading Tao Lin I find myself becoming much drier and flatter. I lose my obligation to feel strongly about anything, especially about how I feel about anything.

Tao Lin is indeed kind of a hipster writer. He’s easy to hate. I think when people say something is “polarizing” that thing often itself has an intense focus on neutrality. Tao Lin is one of the best examples of conveying flat affect and anhedonia as currently endemic and kind of pleasant. Some of the key phrases to use in a Tao Lin parody are “neutral facial expression” and “I feel neutral” and “said in Gmail Chat”. If you use these phrases you will be immediately parodying Tao Lin, and you don’t need anything else. Everything he writes is autobiography, or so it seems. Everything is exactly as it seems. It's just one damn thing after another but there are some interesting elisions and refillings of previous story that are perhaps occuring more in Richard Yates.

There are more changes in Richard Yates from his previous style. Someone must have commented on the names of his characters, like how obvious it is that the main character is always Tao Lin but named like Sam or something. So he named the Tao Lin character Haley Joel Osment and the teenage Jersey girl he met on the internet Dakota Fanning. The ages are about right but the great thing about it is you still can’t actually picture the actors as the characters. I now see “Haley Joel Osment” and that represents a Taiwanese-American hipster writer to me. I wonder whether any kind of defamation charges could be brought but it’s too obviously a stunt. I am willing to honestly believe Haley Joel Osment crossed state borders to statutory rape Dakota Fanning, who is variously self-destructive. I do because those are the characters. There’s really a lot of name-dropping in this, which brings up that issue of how much writers have to be literary historians, or just more culturally aware, or whatever.

I’m afraid that it’s almost a homage to the novel’s namesake that Richard Yates has a pretty clear structure and plot, and particularly that it’s about someone simultaneously epitomizing and feeling alienated from contemporary American society. The story is most of the arc of a codependent relationship. In case you don't know what that is, it's when someone stays romantically involved because they feel the other person needs them and the other person (who often has some compulsion or addiction the first person enables) does more of that to get more from the first person. Neither person involved is very good and both are very depressed. What I like about depression in Tao Lin is that it’s not necessarily pathological. Halfway through the book I totally thought he’d impregnated her.

At first it seems like he just emotional abuses her and then it turns out Dakota Fanning’s been secretly binging and purging. I don't think the "spoiler" concept is relevant here. “Haley Joel Osment” comes across as a total dick even though he does sort of know what to do. I like that Tao Lin does that with not-himself. I like the realism about this couple creating their own little world. I want to use the terms “party girl” and “cheese beast” and have someone understand them. I think Tao Lin is a party girl. I am a party girl. I think the worst party girls got into really intense relationships based on mutual social anxiety when they were 22. It’s easy to say the attitude is immature and neurotic, and I want to shrug that off as harmless and ubiquitous, but the impact on “Dakota Fanning” makes it actually more morally conscious than a parody of Tao Lin. But “Shoplifting” already kind of had that underlying moral message. I think a lot of the couple’s professions of need actually sound kind of weird to me because I feel like every time I’ve said anything like that it was very very self-aware.

I don’t know. A lot of what they, and Tao Lin, do say is self-aware, but so dry that there’s no difference. I always feel like the manuscript was written with a lot less capitalization and punctuation, so it’s gone through that transformation already. Tao Lin definitely is being about neutrality in representation as a direction with an impossible goal. That’s too figurative for a Tao Lin parody. I don’t want to tell you what to do with these books but I do think Tao Lin is important to be able to parody.

I wanted to include some quotes from the book but it lost all the highlights I put in before about 2/3 of the way through and I didn’t want to be biased.

Anyway, I guess I like him because he’s familiar. He steals from places near the place where I work, but doesn’t mention stealing from us, which I appreciate. We have a similar social anxiety and detachment, and have our most emotionally intense experiences through internet chatting. He makes me think “I could do that” but this review was my chance to and I don’t think I could, or want to, and neither could that Observer guy.